| | Adaptability | Importance of cropping history when planting barley | Land topography and soil texture | Problem soils | Soil moisture situation | Frost-free period for barley

Adaptability

Of the major cereal crops, barley is the most sensitive and responsive to the environment. Its wide distribution is the result of very wide genetic variation within the crop, with specific varieties adapted to specific environments. While a good variety may be grown over a wide range of environments, it will achieve its maximum production only in its home or a very similar environment. Varieties can be transferred from one region to another, and may perform reasonably well, but the most productive varieties in an area are those bred in that area. While this applies to all cultivated crops, it is more important in barley than in some less sensitive crops such as common hard red spring wheat.

Days to maturity

Maturity in barley is usually measured by the number of days from seeding to harvest. For a particular variety this figure will vary considerably depending on location, season, and date of seeding. It tends to be lower in the southern part of the province because of increased heat units. This is partially offset by longer day lengths as we move northward. (e.g. at Fort Vermilion, the number of days to maturity is less than at Lethbridge.)

Days from seeding to maturity are reduced by late seeding. Plantings of the same variety at dates as much as a month apart may mature within a period of about a week. However, varieties tend to maintain their relative maturities regardless of environment. Maturity differences can be increased or decreased by location, length of growing season, and sowing date, but varieties will mature in the same order, Maturity differences are compressed by late seeding, and varieties that may differ in maturity by as much as two weeks when sown early will mature within a period of a few days when sown late. Yield from the late sowing will be lower because of the reduced length of the growing period, shorter days, and consequent reduction in time available to produce dry matter.

Importance of Cropping History when Planting Barley

Fields that have a history of repetitive soil erosion by wind or water should not be used for cereal production. They should be sown to soil-stabilizing crops of grasses and legumes. Despite the fact that barley is our most competitive field crop, fields with serious weed or volunteer grain problems should only be considered for barley production if the weeds and undesirable grain can be controlled by tillage with herbicides or harvesting the crop early for silage. Serious weed infestations will reduce crop yields and may lower the market grade of the grain as well as its acceptability for feed or malting.

The possibility of disease organisms, toxins and insects being harbored in, or transferred from, the trash of a previous crop, or from the soil to the barley crop, must be recognized. In southern Alberta, when seasonal precipitation is low, the presence of large amounts of residue from a previous canola crop may reduce the yield of all varieties of subsequently grown barley.

Land Topography and Soil Texture

Barley will grow successfully on almost any topography or land conformation that can be cultivated, provided other conditions do not limit growth. Medium textured soils such as loams, clay-loams and silty-clay loams are generally suitable for barley production. Most agricultural soils in Alberta fall within these textural classes. Surveys have shown there is no yield difference between soil zones (dark brown, thin black, black, grey-wooded) but soil texture did affect yield. Seventy-five per cent of the top producers were growing their barley on loam to clay loam soil, compared to forty-five percent of the low producers. Fifty-five per cent of the low group were growing their barley on sandy loam to sandy clay loam, whereas only 25 per cent did in the top group.

Problem Soils

Saline soils

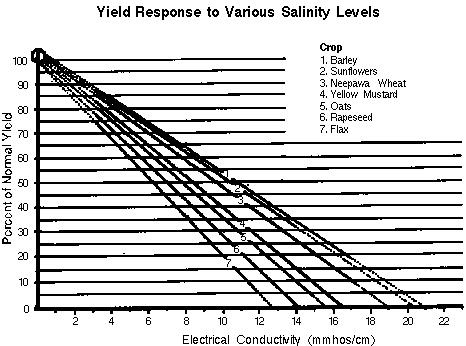

Saline or salty soils that will no longer support the growth of wheat, oats or oilseeds may still be suitable for barley production although yields will likely be reduced. Barley is more tolerant to soil salts than most other cereal crops, and may tolerate as much as 12 mmhos electrical conductivity; spring wheat and oats about 9 mmhos and canola-flax about 6 mmhos. Electrical conductivity is a measure of the total soluble salt concentration in a soil.

There are more than 300,000 ha of saline soils in Alberta, most of which are located in the southern half of the province. Most saline soils have poor internal drainage.

Good barley stands, of somewhat delayed maturity have been grown on soils that contain as much as 1.6% of mixed sodium and magnesium sulphates. Though these are excessively high values, they indicate the possibility of growing barley in special areas if moisture conditions are favorable. Six-row barley generally out-yielded two-row barley which, in turn, outyielded wheat and oats when grown on saline dryland soil in southern Alberta. Generally, the more saline the soil the greater the difficulty in growing any crop - even barley. Saskatchewan Department of Agriculture data gives an indication of the yield response to various salinity levels among seven different crops. The steeper the slope line the less tolerant the crop. Note that the solid portions of slope lines are known values. The dotted portions are projected values.

Acid soils

There are more than 3.5 million ha of agricultural soil in central and northern Alberta where barley yields are reduced by soil acidity. Soil acidity can be determined by any reputable soil-testing laboratory and is expressed as a pH value. A pH value of 7.0 is neutral. In practical terms, a soil below pH of 6.5 is called 'acid', and above 7.5 is 'alkaline'.

The following is a list of crops showing the lowest pH value they will tolerate without yield reduction:

Acidity Tolerance of Various Crops

Alfalfa, sugar beets | 6.5 |

Barley, red clover | 6.0 |

Canola, wheat, corn | 5.5 |

Potatoes, rye | 5.0 |

Cranberries, oats | 4.5 |

More than 30 per cent of the soils in the Peace River region of Alberta have pH values of less than 6.1. In the thin black and dark brown soils north of the Bow River, 28.0 and 19.9 per cent, respectively, have pH values less than 6.1. Though barley varieties differ in sensitivity to soil acidity, all varieties grown in Alberta appear to be less tolerant of acid conditions than oats, wheat or canola. It is difficult to obtain high yields of barley on strongly to very-strongly acid soils (pH 5.5 to 4.5) without first liming the soil. Yields of barley grown on such acid soils have been increased by as much as 15 per cent when lime was added to the soil, provided phosphorus was not limiting.

A small percentage of the surface soils in the brown soil zone of southeastern Alberta are slightly acidic, but the yield response to added lime on these soils is very small.

Solonetzic soils

Solonetzic soils, with their inherent variability and physical conditions, present management problems that are unique. They are often called "burn out or hardpan soils", and are characterized by a tough, impermeable hardpan, that may be 5 to 30 cm below the soil surface. This hardpan layer severely restricts water and root penetration below the topsoil.

With careful management, reasonably good crops of barley can be grown on all but the most strongly developed solonetzic soils. Special attention must be given to surface drainage, time and method of tillage, seedbed preparation, seed placement and crop fertilization.

Where barley is grown on irrigated solonetzic soils, it is important to maintain the soil at the correct moisture content by proper irrigation scheduling. Frequent light irrigations are required to maintain soil moisture levels higher than in normal soils. Centre pivot sprinkler systems appear to be ideally suited to meet the special requirements of irrigating these soils.

Soil Moisture Situation

In Alberta, most barley is grown on dryland. The decision to seed barley should generally be governed by a knowledge of the amount of moisture that will normally be available to the crop, either as soil-stored moisture, or as rainfall to be received during the growing season.

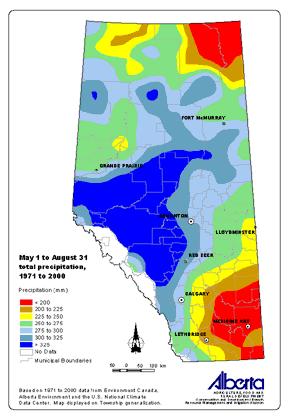

Barley needs about 250-300 mm (10-12 in.) of water to produce a satisfactory crop on dry. When it is grown on irrigated land it will use about 390 mm (15.4 in.) of water for feed and 430 mm for malt. In most of the thin black, black, and grey-wooded soil zones of Alberta, seasonal precipitation (May 1 to Sept. 30) exceeds 250 mm, and annual precipitation exceeds 400 mm. This rainfall provides nearly enough moisture to grow barley annually without relying on stored soil moisture which is normally present. Barley can be grown successfully in these regions.

In parts of the dark brown and brown soil zones, seasonal precipitation may not be adequate to meet the needs of a barley crop without relying on stored soil moisture. Stored soil moisture therefore is very important. High temperatures and drought at heading can negatively affect barley yields and is more likely in the southern parts of Alberta.

The amount of water that can be stored in a soil depends on the texture of the soil. It can be calculated roughly by measuring the depth to which the soil is moist. Moist soil will form a ball when it is squeezed in the hand. The amount (cm) of plant available water stored in equal depths of the various textural classes of soil is shown in the following table.

Stored Soil Moisture

| Approximate depth of plant available water in soil |

Soil texture | cm/30 cm soil | inches/foot soil |

Heavy (clays and silty clays) | 5.0 | 2.0 |

Medium (clay loams, silt loams, loams) | 3.75 | 1.5 |

Coarse (sandy loams and sands) | 2.5 | 1.0 |

From a knowledge of stored soil moisture reserves and expected average growing season precipitation one can assess the advisability of seeding barley on stubble land or on fallow.

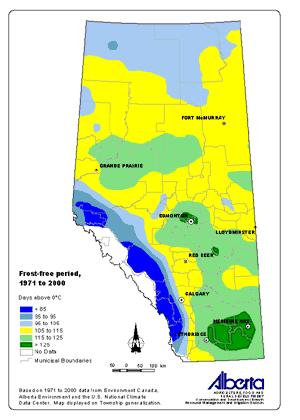

Frost-Free Period for Barley

The average length of frost-free period in parts of the Peace River region and much of the southern third of Alberta ranges from 90 to 130 days. Under good management, and in most years, there should be little or no difficulty in maturing the recommended varieties of barley for Alberta in these areas.

At higher elevations, along the western boundary of the province, and in other localized areas, the frost-free period is often too short to properly mature barley. Some barley may be grown in areas with less than about 90 frost-free days, but producers should expect frost damage to the partially filled heads in the fall. In the spring, frost damage to barley seedlings is usually not severe enough to kill the plants, though they may be retarded a few days and frost damage reduces yield. |

|