| | There is no magical number of live plants that determines whether one should leave a partially winterkilled stand for grain production or not, as many production factors have to be considered.

For example, if the field is situated in a normally dry area of Alberta, one would tend to keep a stand with fewer live plants than if the field were in an area that traditionally had adequate spring moisture. In a dry area, by the time the remaining rye is removed from the field and the new crop is seeded, the seedbed would likely become so dry that very poor germination would result. Unless timely rains occur, the yield would be as poor, or worse, than if the light stand of fall rye were left.

Fall rye has a very good tillering ability, which helps compensate for wide variations in plant population densities. As a rough rule of thumb, in southern Alberta five to six live plants per square foot and seven to eight in central and northern Alberta are adequate to justify leaving the stand. The ideal plant population for both north and south is about 20 to 24 live plants per square foot. With the new, hybrid rye varieties, plant populations above the 16 to 18 plants per square foot provided no yield improvement.

To determine the number of live plants in the spring, wait one or two weeks after growth has begun, and then dig up a few plants and examine them for new root growth from the crown. The new roots are pure white and thicker than the roots formed the previous fall. If new spring root growth is present, even though the leaves are dead, the plant will recover. In some cases, new leaf growth from the crown will be seen but no new root growth. A plant in this condition will likely die as soon as it uses up the food reserve stored in the crown.

If an earlier spring determination of survival is desired, remove a few plants from the field on a warm day. Be careful to protect the plants removed if the air temperature is lower than the soil temperature at the time of removal. If the air temperature is below the plants’ minimum survival temperature at that particular stage of winter hardiness, the plants will die. This outcome would lead to a false conclusion as to the extent of crop injury.

Bring the excavated plants into a warm area of the house, place the crowns in a moist paper towel (or place in sand, soil, cloth, etc.), cover, and allow to grow. Make sure the paper towel does not dry out at any time.

Live plants can be identified in a few days by the presence of new white roots growing from the crown area.

If patchy winter survival occurs, the farmer must assess what amount of survival is acceptable, realizing that the areas winterkilled will likely become troublesome weed patches. When only a few small scattered bare patches exist, some farmers suggest sowing fall rye or winter wheat in these patches as a weed control measure. The winter rye or wheat will stay in a low vegetative state allowing unhindered harvest operations. If many large patches occur, it may be more economical to seed these to spring rye, recognizing the inconvenient harvest situation created by having crops mature at different times.

If damage is extensive and a decision to reseed is made, the surviving fall rye plants should be removed as soon as possible to minimize loss of moisture, tieup of soil nutrients and to facilitate early seeding of the spring crop. In addition, cultivation will minimize the chances of phytotoxic poisoning (plant-to-plant poisoning) of the new crop, which can occur with fall rye residues. Phytotoxic poisoning is also reduced by seeding immediately after destroying the winter crop and preparing the new seedbed.

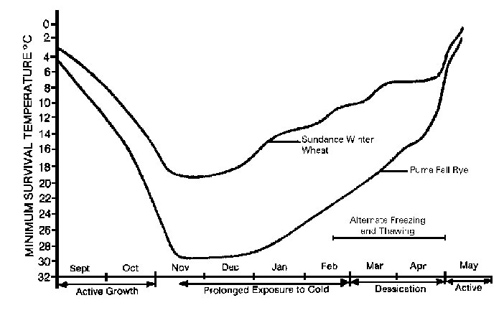

Figure 3. Changes in cold hardiness of winter wheat and rye for the period September to May. The primary factors responsilble for these changes are shown at the bottom of the graph.

Source: Crop Development Center, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon.

More Information

For additional information see the Alberta Agriculture publication Fall Rye Production, Agdex 117/20-1.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to express a sincere thank you to Walter Yarish, Tim Ferguson, Ieuan Evans, Mike Dolinski, Doug Penney, J. Thomas, Don Salmon, Bob Nelson, Grant McLeod, Keith Briggs, Dave McAndrew, Myron Bjorge, Bob Wroe, Russel Horvey, Alan Toly, Bob Wolfe, Blair Shaw, Bill Chapman, Wayne Jackson, Larry Welsh, Ellis Treffry, Gordon Hutton, Allan Macaulay, Mike Rudakewich and Lu Piening for their constructive criticism in reviewing and improving this manual.

A special thanks to Arvid Aasen who wrote, with the help of Ken Lopetinsky, Vern Baron, Ellis Treffry and Myron Bjorge, the pasture, the hay and silage section.

Prepared by:

Murray McLelland formerly with Alberta Agriculture and Rural Development

Revised by:

Harry Brook, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Source: Agdex 117/20-1. Revised June 2018. |

|