| | Description | Biology | Identifying raccoon damage | Control | Trapping | Exclusion

In the last decade, raccoons have become an agricultural wildlife nuisance in Alberta. Raccoons thrive in close association with man, and their numbers are increasing in the urban fringes. This is particularly true in areas south of the Bow river and the South Saskatchewan river. As raccoons become more abundant in Alberta, problems of bird depredation, disease transmission and agricultural damage will increase.

Description

Adult raccoons weigh from 5.5 to 16 kg (12-36 lb). They are easily identified by their black face mask and their distinctive tail, which has alternating yellow and brown rings. The body fur of raccoons has a salt and pepper appearance due to the mixture of grey and black fur. Raccoons range in length from 75 to 90 cm, including the 25 cm tail.

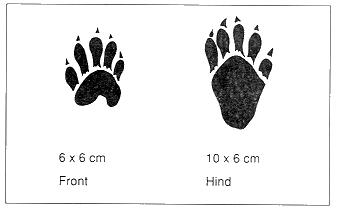

Usually the presence of raccoons is confirmed by footprints found in mud or dirt. The toes and non- retractable claws of the raccoon foot leave an impression that resembles a print of a miniature human hand.

Biology

Raccoons feed on fruit, vegetables, berries, grain, insects, frogs, birds and small mammals. They prefer to live near water sources such as lakes, rivers, marshes or streams, using the natural cover of trees and shrubs.

Raccoons will readily adapt to farm settings and use haystacks, culverts, abandoned burrows and old buildings for protection and as dens to raise their young.

Raccoons breed during late winter. After a two-month gestation period, young are born in mid April to early May. The average litter size is three to six kits, with only one litter per year. Female raccoons can successfully breed after their first winter. Adult females have a home territory of 16sq.km, while adult males have territories that range up to 52 sq. km.

Identifying Raccoon Damage

Raccoons are usually more of a nuisance than a cause of serious economic losses. Homeowners are bothered by the garbage and debris that raccoons will spread around yards. Raccoons eat and contaminate feed, seed and livestock supplements with their feces and urine. Buildings may be damaged by raccoons as they rip shingles and siding off to reach food sources.

Raccoons also damage gardens and field crops. They feed on melons, strawberries, peas and potatoes, and they are especially fond of sweet corn. Raccoons damage corn by climbing the stalks and breaking stalks to reach the ears, pulling back the husks and partially eating the cob.

Raccoons will attack poultry and are able to bring down birds as large as turkeys. They can pull down unsuspecting chickens by reaching through the mesh wire fence. Raccoons are also very adept at gaining access to weakened or open areas of a poultry pen.

Signs of raccoon predation on poultry include carcasses with missing heads, bites on the back, torn necks and breasts, and feeding on the breasts and entrails.

Control

The Alberta Wildlife Act classifies the raccoon as a non-game mammal. Raccoons may be hunted without a licence using a gun or trap at any time of year. A hunter can be the landowner or occupant of the land or a person authorized by the owner or occupant to hunt on that land. Because raccoons are nocturnal animals, shooting is not a highly successful method of controlling them.

No poison is registered in Canada for raccoon control.

Trapping

Raccoons can be successfully removed with a variety of traps. The most effective ways of capturing raccoons alive are with a wire mesh trap or an egg trap. The wire mesh trap should be 10x12x30 inches in size, which is large enough to hold two raccoons. The trap must be secured to the ground to prevent raccoons from rolling it over and escaping by opening the trap door. Several different kinds of bait will attract raccoons; they include sardines, fresh fish, fried bacon, cat food, chicken eggs or corn on the cob. Trapping success increases if bait is scattered on the trail leading up to the trap.

Figure 1. Wire mesh trap for live capture.

The raccoon egg trap is a humane hand hold trap that is designed to take advantage of the raccoon's inquisitive nature and agile front paws. Lures such as jam, syrup, marshmallows or fish work well. The traps are available from some agriculture, and fish and wildlife offices or from the manufacturer: Egg Trapp Co. Inc, Box 125, Ackley, Iowa, U.S.A.

Figure 2. Egg trap for live capture

Other effective traps that can be used for trapping raccoons include the conibear #330 body gripping trap or the #1 1/2 or #2 size leghold trap. These are not live capture traps, and their use should be avoided when there is a risk of trapping non-target animals and pets. Place the traps at the entrance to a damaged area or along the trail to it. Often a hole in a chicken coop or barn is the ideal spot to place a trap. A lure scent or food will be required when there is no definite trail or entrance point.

All traps must be checked at least once a day whether they are live capture or otherwise.

Exclusion

Exclusion is another method of preventing raccoon damage by using secure containers, wire mesh or electric fencing. Store livestock feed in garbage cans with tight-fitting lids. Protect poultry by completely enclosing their pens with wire mesh, including the doors, windows and roof.

Electrified fencing may be justified when raccoons cause routine and substantial economic losses in garden plots, corn fields and poultry yards. Raccoons are sensitive to electrical shocks and quickly learn to avoid electric fences. A two-wire fence with the wires spaced 15 cm and 30 cm above the ground is adequate. To obtain better protection, use a three-wire fence with the wires spaced 10 cm, 20 cm and 33 cm above the ground. All the wires are charged and the soil acts as the ground.

Source: Agdex 684-16. |

|