| | What is litter and what functions does it perform?

Litter (also called mulch), is any old plant residue left over from previous years' production in a native rangeland or tame pasture. It can be standing, freshly fallen or slightly decomposed on the soil surface. Litter performs several important functions vital to the maintenance of resource values for livestock forage production, wildlife habitat and watershed protection and so is linked to rangeland health. Litters' light-tan color will tend to reflect the suns' rays, cooling the soil surface and slowing the loss of scarce moisture. Litter also acts as a kind of latticework at the soil surface that promotes infiltration of water. Litter, along with live plant material, slows runoff and creates a pathway for water to flow into the soil. By improving the retention and percolation of water into a range site, soil erosion by water is greatly reduced. Of course, litter will also reduce wind erosion in the same way that stubble will in a grain field, by causing the wind to be deflected upwards and by capturing any airborne soil particles. The litter layer reduces soil exposure to weedy plant species and insects like grasshoppers that might take advantage of such conditions to establish new plants or lay eggs. As soil microorganisms break down the litter to humus, nutrients are recycled to support plant vigor and growth thereby reducing (tame pastures) or eliminating (native pastures) the need for costly applications of fertilizer.

Photo 1 Healthy mixed grass prairie, maintained during drought.

Even in severe drought, litter reserves have been protected on this grassland.

For the producer, having enough litter means more moisture is available for plant growth, especially during dry periods. Recent studies show that without litter, forage yields will be reduced by about 50% in the brown and dark brown soil zones and by about 30 % during dry years on foothill ranges. We routinely see these types of yield reductions after prescribed burning or wildfires that tend to consume most of the litter reserves.

Of course, in very severe drought, no amount of litter will cause pastures to grow, but adequate litter will mean a faster recovery when drought breaks. Recent experience in southern Alberta showed rapid recovery of pasture production where litter reserves had been protected. Where litter was depleted, pasture recovery is much slower, possibly spanning many years.

Litter can be considered a kind of 'forage bank'. Carryover can be grazed along with new growth in drought periods to supplement livestock forage requirements. Care must be taken in these situations to maintain adequate litter levels at all times - do not empty the bank!

What about forest rangelands?

The LFH layer - (Litter - Fermenting - Humified) in forest range provides a similar benefit to litter on native grassland or seeded pastures. In forest sites, the LFH is composed of fallen leaf, twig and woody materials in three stages of decomposition. A healthy LFH layer is important for forage growth in forest rangelands since plant growth is fully dependent on the nutrients provided by this organic layer. When the LFH is reduced and/or compacted there is increased risk of erosion, reduced soil moisture retention, and fewer nutrients available for plant growth. To producers this can mean less forage and browse produced. The LFH layer becomes compacted by grazing activities when forest pastures are grazed continuously, at heavy stocking rates and without effective rest. Other human or natural causes, such as recreational activities, timber harvesting, fire and insects can also affect the LFH layer.

Producers who graze forest pasture know that when tame pastures show drought effects, healthy forest pastures often remain productive. Producers with a mixture of tame and forest rangelands can rely on the forest component to lessen the effects of drought on their operation. However, this buffering effect can be diminished when the LFH layer is compacted and reduced or forest pastures are unhealthy.

Photo 2 In forest rangelands, the LFH thickness

helps gauge rangeland health.

How much is enough?

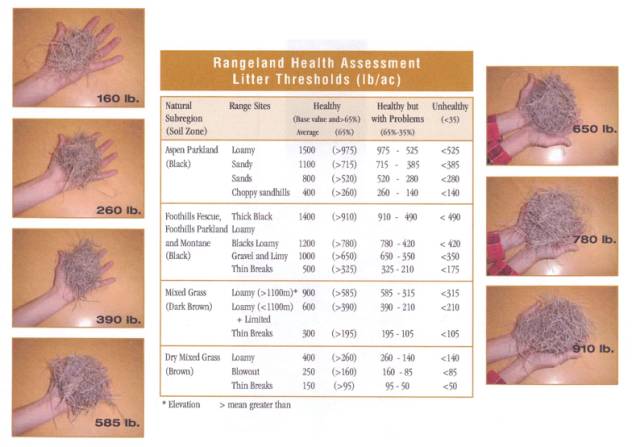

We have developed some practical techniques for judging litter and LFH levels on grassland, forest and tame pastures. In native grasslands and tame pastures, how much litter you should have depends on how much a site will normally produce. The attached table and photos illustrate a simple method to judge current litter levels on native grassland. Pick a number of representative areas in a pasture unit and mark off a 50 x 50 cm plot at each location (you can also use a ¼ meter square metal or wooden frame). Rake up the old plant residue from the plot. Do not include plant material from the current growing season. Compare your litter sample to the appropriate value in the table. You want to have 65% or more of the litter normal for your soil type. On tame pastures, a distinct litter layer should be present on the site. Hand raking a plot this size in a healthy tame pasture should produce at least 1/2 to 1 handful of litter (approx 250 to 450 lb/ac).

On forest range, the LFH thickness will vary naturally, depending on factors like climate, location, soil and plant community. Thickness and compaction can be measured by probing the LFH with a pencil in representative grazed areas. (The 'poke test' is described on page 48 of the Rangeland Health Assessment for Grassland, Forest and Tame Pasture - Field Workbook.) Compare the thickness in these areas with forest sites that are lightly or ungrazed. To score as healthy, the LFH should be no more than 30% thinner and not significantly more resistant to penetration (<50% more effort required) than on lightly or ungrazed areas.

Is it possible to keep too much litter in the 'forage bank'?

Yes and no. Climate and plant characteristics cause litter to accumulate and break down at different rates. In the drier parts of the province, such as the Dry Mixed Prairie in southeastern Alberta, it is not possible to accumulate too much litter. There, local climate conditions restrict plant growth, and increase the rate of litter loss and/or break down. In grassland areas where moisture is less restricted and wind is not a factor, it maybe possible with very light or nonuse of forage to accumulate too much litter. In this case forage production will likely be temporarily reduced due to shading. In forested rangelands the addition of plant materials does not exceed the rate of decomposition so it will not be possible to have too much litter (LFH). Overall, the benefits of litter retention far out weigh any potential risk forage production loss.

*For further information on Rangeland and Pasture Health Assessment documents go to our website.

- Rangeland Health Assessment for Grassland, Forest and Tame Pasture - Field Workbook

- Range Health Assessment Field Worksheets for Grassland, Forest and Tame Pasture

Or, to obtain copies of these documents, contact your local Rangeland Management Branch office, of Alberta Sustainable Resource Development (On the RITE line: 310-0000).

Rangeland Management Branch, Alberta Sustainable Resource Development |

|