| | Damage | Life history and description | Control

Several species of wireworms, Limonius spp., can feed on sugar beets during the growing season and cause reduced plant growth or death of the plant. The variation in species present, differences in habitat and biology, and problems in detection make it difficult to predict when this insect will become a problem. Wireworms feed on many different crops, and sugar beets are particularly susceptible to feeding injury.

Damage

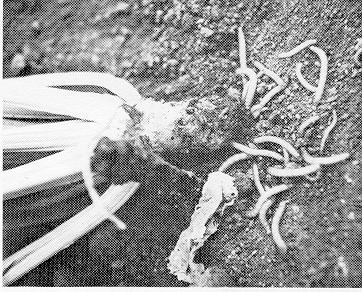

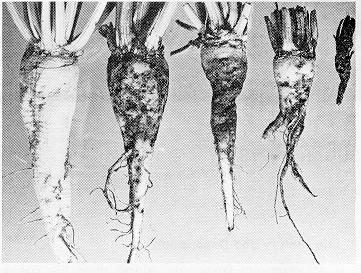

Wireworm larvae feed on sugar beet seed, reducing germination and the plant stand in the spring. Larvae also feed on the roots of seedlings and mature sugar beets. The tap root of seedling plants can be completely eaten or destroyed, resulting in death of the plant during unfavorable growing conditions. When growing conditions are better, secondary roots develop when the main tap root is damaged. Tunnelling and scarring of the root surface is also common. Girdling tunnels that wind all through the root and along its surface may be seen on mature sugar beets. These tunnels appear dark in color, almost black, and may be moist, indicating "bleeding" or loss of plant fluids.

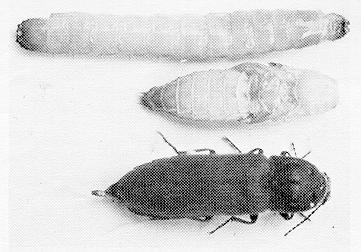

Figure 1. Larva, pupa, adult.

Life History and Description

Wireworm larvae, depending upon the species, require anywhere from 2 to 6 years to complete development before forming pupae in late summer or early fall. Wireworm eggs are laid in the soil during May or June in many field crops, and especially in grassland areas. Wireworm larvae migrate downward late in the season as the soil becomes hot and dry. In the tall, depending upon the time of development, the larvae enter the pupal stage and after 3 to 4 weeks, adult beetles form. Wireworms therefore spend the winter as newly-formed adults or as immature larvae. In the spring, the larvae continue their feeding on plant roots, while the adult beetles emerge, mate, and lay eggs.

Wireworm eggs are small (less than 1 mm), opaque, and are difficult to observe in the field without the aid of a magnifying lens. The larval stage is 18 to 22 mm in length at maturity, white to dark brown, and hard-bodied. They appear somewhat flattened in shape, are many- segmented, and have a notch in the last (tail) segment. They have 3 pairs of short legs, located on the segments near the head. Pupae are 12 to 15 mm in length and appear white to shiny yellow. The legs are folded tightly against the underside of the body and this stage remains inactive in the soil.

Figure 2. Wireworms and wireworm-damaged sugarbeet.

The adult beetle is 6 to 15 mm in size depending on the species. It is light brown to black, elongate, and has two hard wing covers. Adults will "play dead" if disturbed and when turned onto their back, will spring into the air with an audible "click" sound. This click mechanism has given rise to their common name "click beetles."

Figure 3. Healthy beet (left) and beets with various amounts of wireworm damage.

Control

Crop rotation and cultural methods usually prevent wireworms from becoming a major problem in sugar beet fields. Because sugar beets are normally grown in a 4 year rotation in Alberta, crops less susceptible to wireworm attack can be grown on infested fields so populations will not build up. Root and row crops, such as potatoes, corn, onions, or beans, should not be grown in rotation where wireworms have been a problem. Wireworms can also be present when sugar beets are grown on land previously uncultivated or planted to grass or pasture. Deep ploughing in the fall and frequent cultivation in early summer is suggested when wireworms are known to be present in these fallowed fields.

Insecticides can also be used to reduce the wireworm threat. Use of seed treatment chemicals with a cereal crop in rotation with sugar beets is recommended for reducing wireworm populations in a problem field. Granular insecticides applied during sugar beet planting can also reduce wireworm populations and provide early season control. Chemical soil treatments, however, are usually not profitable unless populations of wireworms are high and extensive damage to sugar beets is imminent.

Prepared by:

G. H. Whitfield and A. M. Harper, Agriculture Canada Research Station Lethbridge |

|